Like a Parisian flaneur, I woke up with a headache from too much wine and meaningless pondering. I planned to dive into symphonic work but alas, my current constitution doesn’t allow such endeavor. Instead, we’ll continue to focus on the elegance of the romantic era piano. Grab yourself a cup of coffee or tea and dive in!

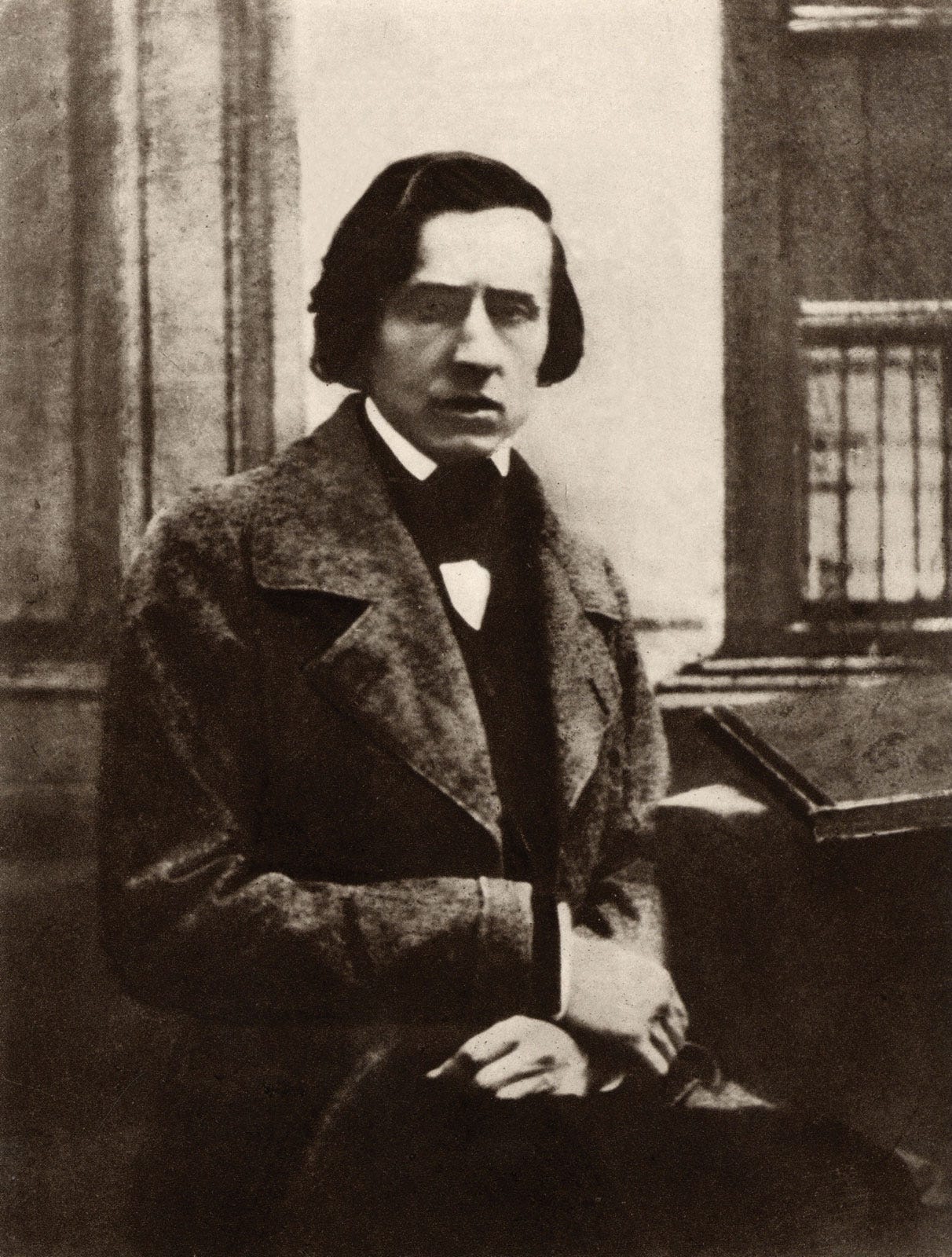

Loud softness. This paradox is what describes the life, work, and personality of the Polish composer.

Frederic Chopin, a beloved musician and an intriguing human, managed to capture the psyche of humanity inside a few bars of melody.

You’ve certainly listened to his nocturnes, the famous Ballade from “The Pianist”, and the rhythmic waltzes.

But this issue is about what I consider his most ingenious work. Certainly his most revolutionary composition:

The Études

An étude is a study of a specific technique on an instrument. Usually short but demanding, it’s structured in a way that allows the soloist to practice a variation of a passage repeatedly.

Think of them as chess puzzles or football drills but for musicians.

Chopin, being who he was, decided to take this “form” and create beautiful compositions that not only served as training but they were complete musical concepts. Often containing more depth than full-fledged sonatas.

I’ve mentioned in a previous issue that Chopin was perhaps the only composer who truly escaped the grip of the Giants. Even though he admitted numerous times of their influence, the 27 études revolutionized the piano and created a new paradigm.

Perhaps there are greater performances than Pollini’s. But none of them is as clean and vivid as his. A great introduction.

There are 3 sets of études. Op. 10 (12 études dedicated to Liszt… and inspired him), Op. 25 (12 études dedicated to Marie d’Agoult, Liszt’s “unofficial” wife"), and 3 more that are missing from this recording, part of a book on the method of piano.

You’ll notice that these compositions maintain a rigid structure, yet they’re decorated by the most beautiful, fiery melodies you’d never expect to hear in a set of exercises.

One of my favorites is the No. 4 from Op. 10. The Torrent.

Fluid and wavy. It’s devilishly difficult and hard to make sense. But the Russians have managed well, with Horowitz taking the first seat.

Richter isn’t far behind. Notice how different is his interpretation. Feverish, trying to run away. (Poor sound quality but endure!):

(Worth looking at Kissin’s and Lisitsa’s performances too)

Ocean. No. 12 from Op. 25.

The up and down dynamic creates the illusion of submerge-immerge during a storm in the middle of an ocean. The hopeful breaks represent the glimpses of the sun only to return to the fury of the sea.

At 1:42, the change in scale is a turn for the worse. And then, liberation. Hope becoming reality.

Winter Wind. Étude Op. 25, No. 11.

Minimal movement. Light wind. And then…

At 00:23, the snowstorm ensues. I always imagine icicles vibrating, producing this cascade of chromatic hammering.

Then, renewal. Nature cleansed itself from the wastes of autumn.

Revolutionary. Étude Op. 10, No. 12

Again, ignore the poor quality. Observe the pathos of Richter in the beginning. Preparing to play something hard, painful: Étude on the Bombardment of Warsaw

The failed revolution of Chopin’s birthplace, Poland, against Russia.

Supposedly, Chopin didn’t expect this. The piece contains celebration, heroism but also an expectation of failure. It ends abruptly, the same way it began.

CODA

Forte Pianissimo. Loud Softness.

There’s a distinctive, poetic inspiration in Chopin’s work. His ability to create impactful, “loud” music through subtle “soft” melodies is unmatched.

His work was revolutionary and changed music for the better. Personally, I have a love-hate relationship with him. I admire his work but too much Chopin will recreate the cloying, melancholic environment of his Parisian life.

It’s best to balance this with more heartful music and keep Chopin for rainy days or silent nights. Or when it’s time for revolution.

Share this with every musician, uninitiated pop listener, classical music connoisseur, snob aristocrat, the bourgeoisie or proletariat:

Beautiful. Chopin's music is subtly powerful exactly as you say, but I couldn't agree more about the melancholic feelings it can bring over you.

If you really sit down and listen to them, the power is just immense. The Ocean No.12 in particular made me stop in my tracks, and I just had feelings of sadness and desperation wash over me for the two minutes, and then it was gone.

Coming back to baseline after that is a strange feeling, but it's pieces like that which have given me a stronger appreciation for Nietzsche and his writings on music - which I had read, but never fully grasped until quite recently.

I really enjoy the cues for what to listen for in each piece as well, it gives me an excuse to re-listen with a closer attention to the details - and the comparisons of each artists interpretation of the pieces.

I was discussing this recently with my girlfriend, who couldn't understand how there could be differences in how pieces were played if it's all coming from the same original sheet music - I will use this post to illustrate why.

Great edition as always, looking forward to the next!